The Christology of “A Knight's Tale”

There will come a time in life when the truths you believe seem impossible to grasp. The world will shout you down and the feelings of passion that you mistook for faith will fade into memory; like a lost love who seemed to take more of you with them than they left behind. Moving forward will seem dishonest. The choice often made in response to these feelings is to simply fold and fall in line for stale bread and watered down soup, and in a purely humanistic framework this makes sense. Why should we doubt the immutability of person’s feelings, even if those feelings are darker than our nightmares? Nightmares, as bad as they are, can at least be woken up from.

While there is a time for questioning our framework, there is a lazy way to do so that masks timidity with false nobility. It is far too easy to relinquish an idea we cannot grasp without first asking if we lack the strength to grasp it. There is a scene in Brian Helgeland’s A Knight’s Tale where the squire-turned-knight William Thatcher is gasping for breath in the jousting arena at the tournament games in London. His rival has just struck him with an illegally tipped lance, leaving a wound that obliterates the strength in his right hand. William tries uplifting his lance but cries out in pain and drops it immediately. He has already foolishly removed his armor, unable to breath with it on, and to take part in the joust exposed and empty-handed spells obvious doom to his friends who fully expect this to be the end of their unlikely journey from obscurity to glory. The only way to win in this final round is to knock the rival, Count Adhemar, clean off his horse.

“Lash it to me arm,” he tells his friend, Wat. His friends look at him incredulously, torn between two different kinds of love for him: the love that desires for his security, and the love that secures his desire. They eventually do his bidding, using a strip of leather to strap the weapon to William’s lifeless forearm, so that he might hold what he cannot grasp.

For those unfamiliar with this overtly charming and covertly deep film, I’ll go back a ways. It opens with William, Wat, and Roland discovering that the knight they’ve been serving for years has kicked the bucket while defecating behind a tree. With the joust they were competing in about to recommence, and no other recourse for sustenance, William dons his master’s armor and competes in his place. The trio wins a small prize that they quickly sell in order to briefly quench their appetites. Before parting, however, William convinces his companions to pool their winnings and help him continue the masquerade.

“How did the nobles become noble in the first place? They took it. At the tip of a sword. I’ll do it with a lance.”

“A blunted lance,” Wat retorts.

“No matter what. A man can change his stars.”

Wat and Roland reluctantly agree, and after they cross paths with the destitute poet Geoffrey Chaucer who agrees to help them forge patents of nobility in return for a piece of the winnings, they begin competing.

William quickly climbs the ranks and becomes a force to be reckoned with in the joust, the most prestigious of the games. Along the way he meets Jocelyn, a woman of noble birth, with whom he falls in love despite continuing to conceal his true identity. He also crosses lances with Adhemar, the arrogant nobleman who lusts for continued domination of the jousting arena as well as the affections of Jocelyn.

During a tournament, William shows mercy to an injured contestant, Colville, by allowing their jousting match to end in a draw instead of finishing him in the final round. At another tournament, Colville is revealed to be Edward the Black Prince; and William honors his choice to participate in the games by riding against him despite the obvious faux pas of risking injury to a member of the royal family. There is a strange kinship between the two: the peasant and the prince, both playing the knight.

The team, joined by the fiery blacksmith Kate, enjoy the winnings and the boisterous camaraderie that comes with their mutual loyalty to each other. This joy, however, is always tempered by the truth of William’s humble beginnings as a peasant. Victory both in tournament and in love is slightly embittered by this perpetual lie.

The lie does not last. William, now known by the pseudonym Sir Ulrich Von Liechtenstein, wanders to his father’s house in Cheapside; his father who gave him up as an apprentice when he was a boy in order to give him a chance at an honorable life. This touching reunion, in the midst of the grand tournament of London, is witnessed by Adhemar who alerts the authorities to William’s deceit. At the behest of his friends and lover, he refuses to run and is arrested, barred from continuing in the climactic tournament, and put in the stocks to be jeered and mocked by the very crowd that had idolized him the day before.

“You have been weighed. You have been measured. And you have been found wanting.” These words from Adhemar ring in his ears and echo in his heart as the voice of his deepest fear: that a man cannot change his stars.

As the crowd grows in their open scorn and aggression toward the humiliated William, a cloaked figure pulls back his hood and approaches the stocks. The crowd is stilled by the commanding presence of Prince Edward, and the son of the king leans down to speak softly to the criminal.

“What a pair we make. Both trying to hide who we are. Both unable to do so.”

He commands William’s release and has him take a knee…

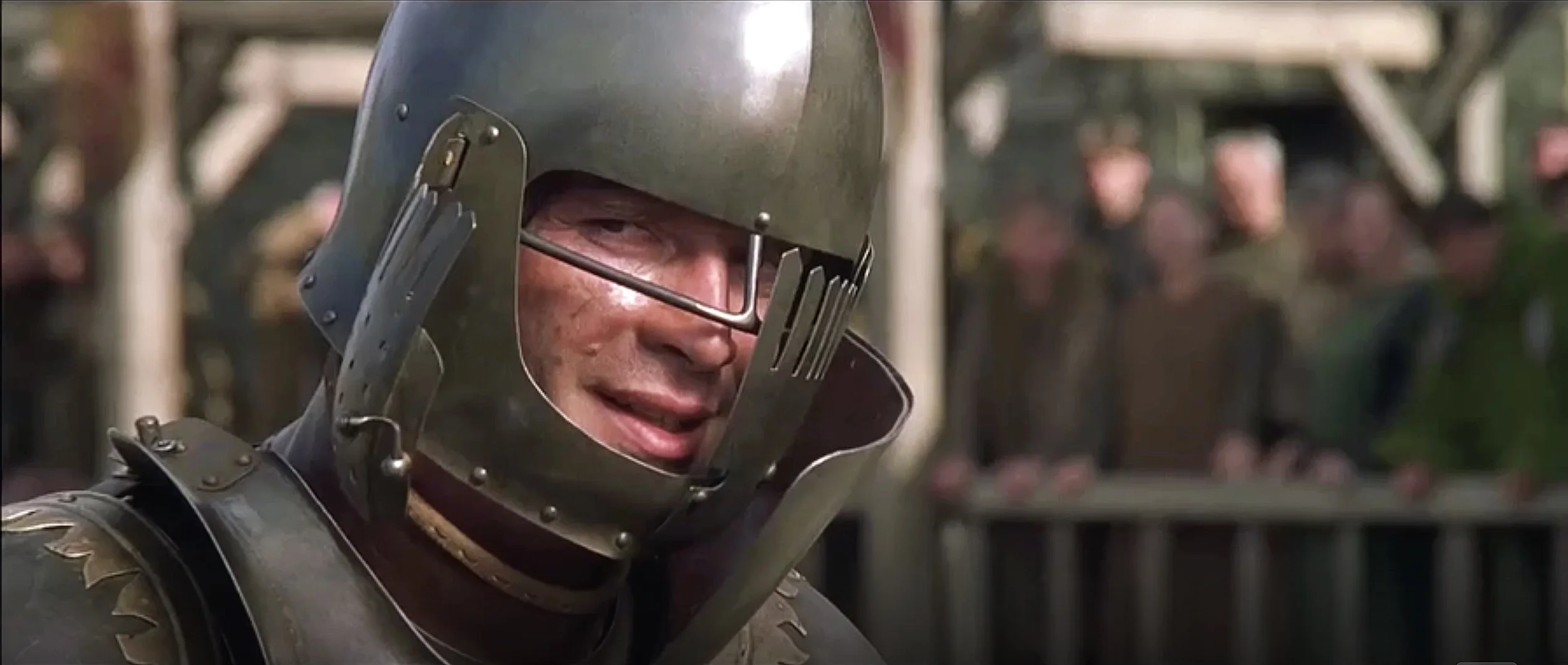

… bringing us to the above frame, which unlocked the heart of this film for me, even after years of enjoying it obliviously. If you’ve read this far, I thank you. I have tried to succinctly as possible provide the context for the subtext, hopefully without pretext. I’ll begin with what I feel should be such an obvious detail, though it took me many viewings to notice. Edward, dressed in an almost monastic coat and preparing to make the son of a Thatcher into a knight, is framed with a cross above his head, engraved on a stone building in the background. As a filmmaker myself, I know that such a blatant image doesn't happen without intent on the part of the filmmaker.

For a while I took it as a nice creative touch, identifying Edward with Christianity and giving spiritual weight to William’s knighting. Upon further review, I’ve found it hard to simply identify Edward with Christian gravitas; but with Christ himself. The seed for Edward’s merciful act toward William was planted in the jousting arena, first in William’s mercy toward him, and second in William’s willingness to joust with him even in his royalty.

“You knew me. And still you rode?”

“It is not in me to withdraw.”

“Nor me.”

I am reminded of the shrewd biblical patriarch, Jacob, wrestling with God in Genesis chapter 32.

And Jacob was left alone. And a man wrestled with him until the breaking of the day… Then he said, “Let me go, for the day has broken.” But Jacob said, “I will not let you go unless you bless me.” And he said to him, “What is your name?” And he said, “Jacob.” Then he said, “Your name shall no longer be called Jacob, but Israel, for you have striven with God and with men, and have prevailed.” Then Jacob asked him, “Please tell me your name.” But he said, “Why is it that you ask my name?” And there he blessed him. So Jacob called the name of the place Peniel, saying, “For I have seen God face to face, and yet my life has been delivered.” (ESV)

“How did the nobles become noble in the first place? They took it.”

Mirroring this, A Knight’s Tale shows us a commoner who has striven with the prince and with men, and has prevailed; at least until his lowly roots are revealed and put to shame. Edward christens him with a new, knightly title, Sir William Thatcher. And all this because months prior, the two men met on the equalizing ground of the dust-laden arena. The only way that William’s exaltation could be legitimized was in The Black Prince humbling himself into a man to be striven with. The idea of the Son of the King descending to walk amongst his subjects in order to invite them into brotherhood is an echo of the incarnation of God into the man, Jesus.

“But as many as received him, to them gave he power to become the sons of God...”

During the ministry of Jesus there are several examples of Him either instructing those He interacts with to hold their tongues regarding His identity as the Son of God, or acting Himself as if the time for this revelation has not yet come. Edward evokes this idea as throughout the film his character builds from disguised in one scene, revealed in another, and actively displaying his authority in the last.

William returns to tournament after his knighting, bringing us back to the scene described at the beginning of this post. He faces Adhemar, like David without Saul’s armor; partaking in the vulnerability of the prince; baring his heart to the enemy; bearing his lance, almost like a cross; and bearing his enemy to the ground.

The doctrine of God becoming a man while maintaining His divinity is not an equation to be worked out, or a riddle to be solved, so much as a song to be sung. This story sings it well. May the reader be willing to hold even that which he or she cannot grasp. And to those who have received Him: He has been weighed. He has been measured. And you have been found holy.

How fitting it is, that the very event which signaled the birth of Jesus Christ was a changing of the stars.